Thoracic OUtlet Syndrome

Taking a Deeper Dive Into Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

In the baseball world, the most common injuries sustained by the throwing arm are well publicized. Rotator cuff and labral tears as well as Tommy John surgery have gotten a lot of focus over the years as major potential risks throwing athletes face as they continue their athletic careers. One of the less commonly discussed injuries which can nevertheless have serious implications is thoracic outlet syndrome. Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a unique condition which many baseball athletes have experienced at some point in their careers. This article will discuss what thoracic outlet syndrome is, how it can impact a throwing athlete’s career, and what can be done to treat it.

What Is Thoracic Outlet Syndrome?

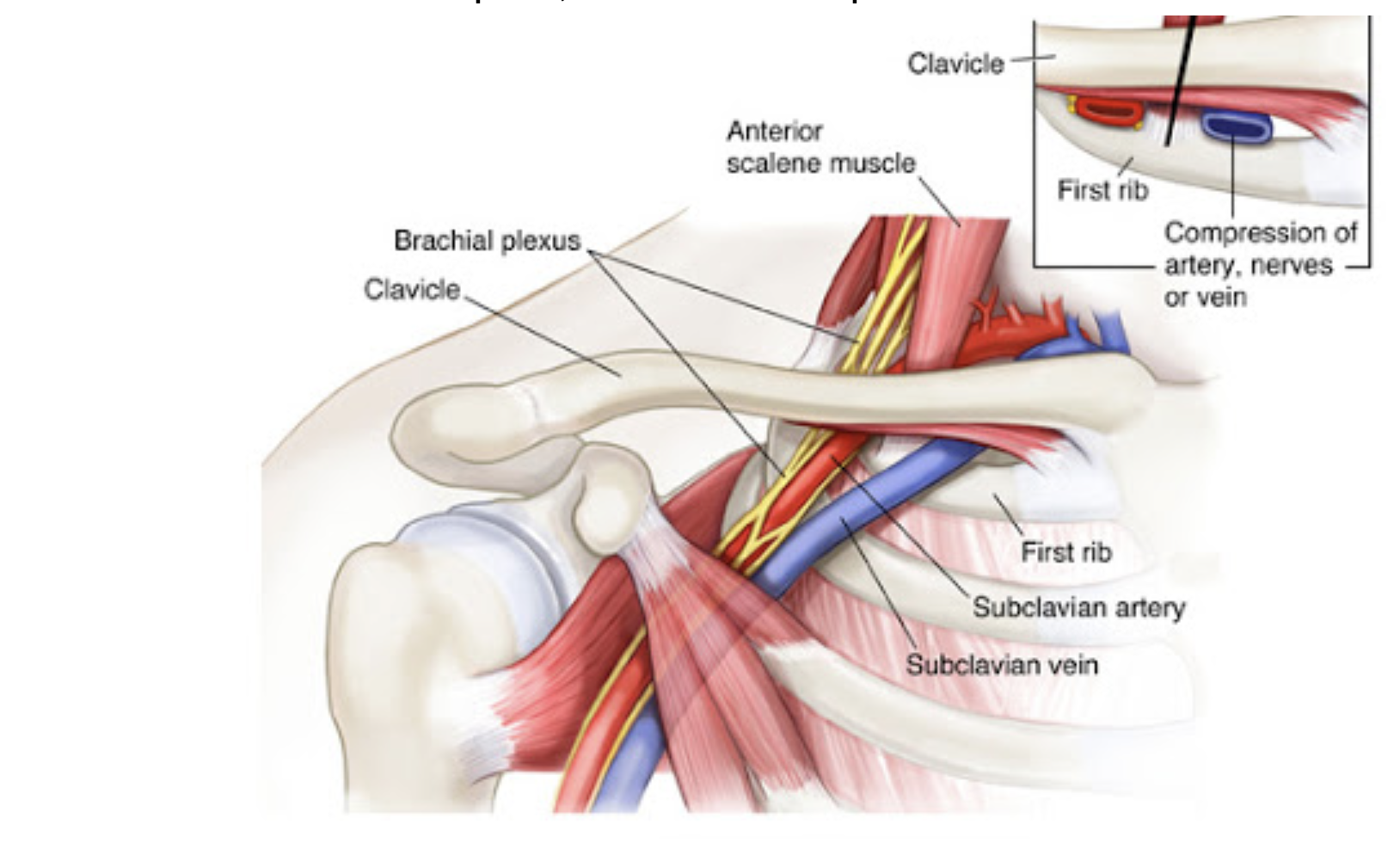

According to Watson et al, TOS is defined as “a symptom complex characterized by pain, paresthesia (numbness and tingling), weakness and discomfort in the upper limb which is aggravated by elevation of the arms or by exaggerated movements of the head and neck.” These symptoms can arise due to compression of the brachial plexus (a large branch of nerves arising from the neck and upper thoracic spine), the axillary-subclavian vein, or the subclavian artery. While the name describes symptoms arising from one specific area, the thoracic outlet, compression can occur in several areas:

The scalene triangle (between the anterior and middle scalene muscles of the neck)

The space between the clavicle and the first rib (this is the true thoracic outlet)

The subcoracoid space, underneath the pectoralis minor muscle

Symptoms can vary depending on which structure is compressed.

The Varying Types Of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS)

Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome is the most common form of TOS, with some studies reporting a prevalence of up to 95% of all cases. Neurogenic TOS occurs when there is some type of irritation, compression, or traction of the nerves of the brachial plexus, degrading their ability to function. Depending on which levels of the brachial plexus are involved, there can be:

Pain

Numbness

Tingling

Weakness

These symptoms can occur in the face, neck, shoulder, scapular region, throughout the arm and into the hand. Tenderness to touch can also be present in the scalene muscles as well as in the pec region. A key characteristic that can differentiate neurogenic TOS from other conditions is that symptoms can often be altered by postural changes, whether that be a change in head position or adjusting the scapula out of a rounded or depressed position.

While neurogenic TOS is the most common variation, compression to the vascular structures is also possible. Venous TOS is the more common of the two non-neurogenic conditions, accounting for around 5% of all cases. Also known as ‘Effort Thrombosis’ or ‘Paget-Schroetter Disease’, this occurs when the subclavian vein (or axillary vein, depending on the site of compression) has been chronically compressed, forming an acute blood clot. Venous TOS is a condition that develops over time. Initially the vein will begin to be damaged by compression, usually with elevation of the shoulder. Scar tissue will begin to develop around the vein, causing compression to that area. Blood flow remains fairly consistent, however, as smaller vessels branch off the vein to allow blood to pass through. That said, after enough consistent compression and damage, even the flow to these smaller pathways becomes restricted and a clot can form. When this happens, pain and paresthesia can occur, similar to in neurogenic TOS. Additionally, there can be:

Swelling

Feelings of heaviness or stiffness

Discoloration (usually a blue color) in the arm

Increased appearance of veins throughout the extremity

This condition generally requires immediate attention due to a chance of a pulmonary embolism, in which a part of the clot can travel to the lungs. While the incidence of this is relatively low, studies report that around 20-30% of venous TOS cases also present with pulmonary embolism, and the condition can be fatal in some instances. Hence, early detection and treatment are crucial.

Arterial TOS is the least common variation, accounting for 1-3% of all TOS cases. The majority of arterial TOS cases involve some type of bony or soft tissue abnormality such as a cervical rib, a deformed first rib, or scalene hypertrophy. As a result of compression on the subclavian artery, a blood clot or even an aneurysm can form. Similar to venous TOS, arterial TOS is characterized by:

Pain

Numbness

Discoloration of the arm

Loss of blood flow to the fingers

Diminished pulse throughout the arm

Now I have a Thoracic Outlet Diagnosis, what do I do?

Now that we have gone over the various types of thoracic outlet syndrome we will get more into the details of diagnosing, treatment and preventative steps one can take to combat this precarious issue. We will discuss how a diagnosis can be reached as well as what steps can be taken to both treat this condition and reduce the likelihood of it occurring in the first place.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Symptoms of the various types of TOS can overlap. Additionally, it is possible that multiple structures may be responsible for an athlete’s symptoms. As a result, diagnosing TOS is not cut and dried, and may present some difficulties. From a clinical perspective, it is important to gain as clear a picture of an athlete’s symptoms and presentation as possible. While there are various in-clinic provocative tests that clinicians can perform, these generally have a high false positive rate and diagnosis should not be based purely off of their results. Oftentimes imaging is required to see which structure or structures may be compromised. There are conflicting reports as to which is the gold-standard, but generally diagnostic ultrasound or catheter-directed venography or arteriography are most commonly used.

There are various aspects to treatment for TOS, depending on which structures may be compromised. In the cases of venous and arterial TOS, generally some type of anticoagulant will be administered to begin to break up the blood clot. Likely surgery will be performed to further help with removal of the clot, potentially reconstruct the damaged vessel, and decompress the areas where compression is occuring. Most commonly this includes removal of the first rib, but it also isn’t uncommon to remove the anterior scalene and subclavius muscle. In some instances where the pec minor is involved with compression, some might recommend cutting its associated tendon. These are also the same areas where decompression may occur if surgery is performed for neurogenic TOS. It has been documented that the outcomes of these surgeries are very good and that athletes have a high probability of returning to their previous levels of competition within a year.

Rehabilitation and Prevention of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

While surgery is usually recommended for instances of arterial and venous TOS, neurogenic TOS can have good outcomes with rehabilitation alone. Cases where the symptoms may be less severe or haven’t been present for long will often be prescribed some form of rehabilitation before surgery is recommended. Taking into consideration that TOS can be the result of compression from the scalenes, pec minor, and under the clavicle, it is important to address everything that can feed into those structures. Improving range of motion throughout the neck, shoulder, scapular region and thoracic spine is key (not to take away the importance of the lower half of the body).

Additionally, an athlete’s breathing pattern needs to be taken into consideration to further address areas of compression. Our ribcage can become more biased to certain positions depending on how we breathe. If we take into account that all of the muscles that have been implicated in the compression of the neurovascular structures associated with TOS also attach to the ribcage, it’s reasonable to assume that breathing may be strongly related to TOS symptoms, especially considering that we take over 20,000 breaths in a single day.

Improving mobility and breathing isn’t the only aspect of rehabilitation for TOS. Rehabilitating athletes also need to regain appropriate strength. We can look at the importance of strength from a few different perspectives. First, a lack of strength can affect how the scapula interacts with the shoulder and thoracic spine. Scapular imbalances and their effect on posture have been shown to be related to TOS symptoms. Improving strength in these areas can help improve posture and movement, which could potentially improve symptoms. From a different perspective, muscles often can become tight because they are weak, especially if they are continually stressed, such as in the throwing motion. While we likely don’t want to immediately work on contracting these spasmic, hypertrophied muscles when symptoms are very acute, it is my opinion that there is benefit to strengthening these areas with the goal of reducing overall tone in the musculature once symptoms have settled.

Thoracic outlet syndrome is a potentially very serious condition, but players can have good outcomes if it is identified early and treated appropriately. Knowing the signs and symptoms as well as understanding the contributing factors is key to reducing the likelihood that its impact is long-lasting. Working in conjunction, medical professionals and a high performance team can take measures to limit the potential for this condition to arise in an athlete and allow them to remain on the field.

How can physical therapy help?

A PT can help educate you on your symptoms, beliefs about movement, breathing, exercise and pain, and how to start to improve your condition.

PTs can provide a strength, range of motion (ROM), balance and coordination assessment of your upper extremities and spine to identity what’s impacting your knee

A PT can assess old injuries and their impact on your neck, shoulder, elbow, and hand.

As manual therapists, we can provide gentle mobilizations and soft tissue work to improve joint mobility and decrease pain. We can help train your joint’s awareness and proprioception so it can handle unexpected stresses and strains with more resiliency.

Physical therapists can design an individualized program with mobility, ROM, and strengthening exercises for your trunk, posture, neck, and shoulder. We can design a daily/ weekly maintenance home program for TOS. A PT can also give you a program for progressive return to activity and progressive loading to facilitate improved tissue strength and tolerance.

AUTHOR:

Terry Phillips, PT, DPT

Physical Therapist and Baseball Specialist

CONTRIBUTORS:

Jordan Bork, PT

Physical Therapist and Baseball Specialist

Joe Midgett, PT, DPT

Physical Therapist and Baseball Specialist

Bob Adams, DO

Sports Medicine Physician and Former head of the medical team for USATF

Avi Goodman, MD

Evergreen Health Orthopedics & Sports Medicine

Vincent Santoro, MD (Retired)

Orthopedic Surgeon and former college pitcher

Ben Wobker, PT, MSPT, CSCS, CFSC, SFMA

Founder & Director LWPT

MORE BLOGS

MORE WEBINARS

References

Chandra, Venita, et al. “Thoracic Outlet Syndrome in High-Performance Athletes.” Journal of Vascular Surgery, vol. 58, no. 2, 2013, pp. 567–568., doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2013.05.086.

Ferrante, Mark A., and Nicole D. Ferrante. “The Thoracic Outlet Syndromes: Part 2. The Arterial, Venous, Neurovascular, and Disputed Thoracic Outlet Syndromes.” Muscle & Nerve, vol. 56, no. 4, 2017, pp. 663–673., doi:10.1002/mus.25535

Hangge, Patrick, et al. “Paget-Schroetter Syndrome: Treatment of Venous Thrombosis and Outcomes.” Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy, vol. 7, no. S3, 2017, doi:10.21037/cdt.2017.08.15.

Otoshi, Kenichi, et al. “The Prevalence and Characteristics of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome in High School Baseball Players.” Health, vol. 09, no. 08, 2017, pp. 1223–1234., doi:10.4236/health.2017.98088.

Sanders, Richard J, et al. “Diagnosis of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome.” Journal Of Vascular Surgery, vol. 46, no. 3, Sept. 2007, pp. 601–604., www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0741521407007343.

Thompson, Robert W. “Thoracic Outlet Syndrome and Neurovascular Conditions Of The Shoulder In Baseball Players.” Baseball Sports Medicine, by Christopher S. Ahmad and Anthony A. Romeo, Wolters Kluwer, 2019.

Watson, L.a., et al. “Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part 1: Clinical Manifestations, Differentiation and Treatment Pathways.” Manual Therapy, vol. 14, no. 6, 2009, pp. 586–595., doi:10.1016/j.math.2009.08.007.

Watson, L.a., et al. “Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Part 2: Conservative Management of Thoracic Outlet.” Manual Therapy, vol. 15, no. 4, 2010, pp. 305–314., doi:10.1016/j.math.2010.03.002.