The Shoulder

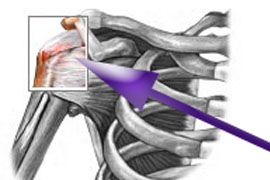

The Shoulder is made up of three bones: the clavicle (collarbone), the scapula (shoulder blade), and the humerus (upper arm bone) as well as associated muscles, ligaments and tendons. The articulations between the bones of the shoulder make up the shoulder joints.

There are two kinds of cartilage in the joint. The first type is the white cartilage on the ends of the bones (called articular cartilage) which allows the bones to glide and move on each other. When this type of cartilage starts to wear out (a process called arthritis), the joint becomes painful and stiff. The labrum is a second kind of cartilage in the shoulder which is distinctly different from the articular cartilage. This cartilage is more fibrous or rigid than the cartilage on the ends of the ball and socket. Also, this cartilage is also found only around the socket where it is attached.

The shoulder must be flexible for the wide range of motion required in the arms and hands and also strong enough to allow for actions such as lifting, pushing and pulling. The compromise between these two functions results in a large number of shoulder problems not faced by other joints such as the hip.

Common Injuries of the Shoulder

Frozen Shoulder

Impingement Syndrome

Labrum Tears

SLAP Lesions

Shoulder Webinars

Shoulder Blogs

Nick talks about the latest in research on stretching both internal and external rotation.

Read:

Ben does an in-depth review of the very common rotator cuff injury and how to best manage it.

Read:

Victor reviews the latest on Seahawks LB Jordyn Brooks.

Read:

Frozen Shoulder

Primary adhesive capsulitis, more commonly known as frozen shoulder, is a largely idiopathic pathology involving two things: spontaneous shoulder pain and contracture.

While the primary cause of frozen shoulder is unknown, what is known is that with the onset of frozen shoulder there is a stimulus in the shoulder that produces tissue changes in the joint capsule. The initial stages of adhesive capsulitis include chronic capsular inflammation causing pain at the shoulder joint. This typically first presents, as pain only at night and with specific movements then over several weeks can become a more constant pain even at rest that gets worse with any movement. The next stage of adhesive capsulitis is known as the frozen stage and includes the formation of capsular fibrosis and adhesions of synovial folds that begin to occur in the shoulder joint causing severe restriction of movement. Normal daily activities can be severely affected during this stage. The third stage is known as the thawing, or regressive phase. In this phase pain progressively decreases and shoulder range of motion slowly begins to recover.

Untreated, the thawing phase can last from 12-24 months although very few patients have any significant long-term functional limitations at the end of this phase. There is also a secondary frozen shoulder syndrome with a known cause. This process typically starts with a trauma or episode of inflammation in the shoulder leading to pain and/or painful spasms. The patient will cease to use their arm due to muscle guarding or pain, which will lead to classic patterns of restricted motion in the joint.Treatment

Treatment must be directed to supporting the individual bones and joints which make up the arch, and to aid the arch in its job as a shock absorber. This in turn alleviates the arch pain, and prevents the further collapse of the arch. This is accomplished through the use of orthotics and proper footwear. Custom-made orthotics gently support not only the arch, but each individual bone and joint which makes up the arch. This not only relieves the arch pain, but prevents it from returning, and keeps the arch from collapsing further.

Treatment

1. Manual Therapy: including passive stretching and joint mobilizations to reduce restrictions in the capsule of the shoulder joint

2. Strengthening: emphasizing postural strengthening and neuromuscular control of the shoulder complex and scapular stabilizers.

3. Home Exercise Program: emphasizing articular stretching and strength-maintenance.

Authors:

Evergreen Health

Vincent Santoro, MD

Lake Washington Physical Therapy

Matt Sato, PT, DPT

Ben Wobker, PT, MSPT, CSCS

References:

Kelley, MJ, et al. Frozen shoulder:evidence and a proposed model guiding rehabilitation. JOSPT. 39:135-148, 2009

Orthopedic Physical Assessment, 4th Edition. David J. Magee, 2006. Rundquist, PJ, et al. Patterns of motion loss in subjects with idiopathic loss shoulder ROM. Clin Biomech. 19:810-818, 2004

Impingement Syndrome

Description:

The shoulder is one of the most mobile joints in the body due to the shallow connection of the humerus (arm bone) to the glenoid fossa (scapula). The shoulder consists of static stabilizers such as the labrum, joint capsule and ligaments. Dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder joint include the rotator cuff, the long head of the biceps tendon, and muscles of the shoulder girdle. Impingement occurs when a tendon of the rotator cuff is inflamed (often because of overhead repetitive stresses) and is compressed under an outlet in the shoulder known as the subacromial space. This space in which the supraspinatus, and biceps tendon pass under decreases significantly when raising the arm overhead causing a painful arc of motion when the tendons or bursa are compressed under the acromion process. This mechanical impingement can result in pain at the shoulder, especially with overhead activities or reaching behind ones back. Normal mechanics at the shoulder can also be disrupted which limits ROM and prevents normal biomechanical movement of the humerus and scapula together (known as scapulohumeral rhythm).

Symptoms:

Normally an impingement will feel like a dull or sharp end point in the shoulder range of motion. Most commonly this is noticed when reaching over head into cabinets or work related movements. This can also be present when dressing, working out, and swimming.

Treatment:

Manual Joint Mobilization: to restore normal arthrokinematics at the shoulder complex and reestablish non-painful ROM

Strengthening Program: targeting the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers emphasizing neuromuscular control of the shoulder complex. Postural stabilization and education are also important in reestablishing proper biomechanical movement.

Modalities: as indicated to reduce pain and inflammation at the shoulder joint

Authors:

Evergreen Health

Vincent Santoro, MD

Lake Washington Physical Therapy

Matt Sato, PT, DPT

Ben Wobker, PT, MSPT, CSCS

References:

Orthopedic Physical Assessment, 4th Edition. David J. Magee, 2006. Millar, AL, et. al.

Epidemiological study of incidence of shoulder conditions. JOSPT, 36: 403-414, 2006

www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/92974-overview

Rotator Cuff Tears

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles; the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and the teres minor. These muscles work together to act as dynamic stabilizers for the shoulder complex. They also assist in the normal mechanics of the shoulder joint by depressing the head of the humerus when raising the arm overhead, which helps prevent impingement from occurring. Rotator cuff tears typically occur at the junction where the tendon attaches to the bone and are can be caused by both extrinsic (outside) and intrinsic (inside) factors.

Outside factors include acute trauma to the shoulder caused by a fall, or overuse injuries from repetitive activities that require pushing, pulling, or throwing. Intrinsic factors include poor blood supply and degenerative changes. Chronic degeneration is the most common cause of rotator cuff tears among persons who are greater than 40 years of age.

Tendon degeneration can be classified in 3 subsequent stages:

Stage 1 is the occurrence of edema and hemorrhage.

Stage 2 is signified by fibrosis and tendonitis.

Stage 3 is an actual tear of the rotator cuff.

Symptoms of rotator cuff pathology include shoulder pain, especially with overhead movement or after a traumatic incident. Weakness is almost always present as well due to the compromised tendon to bone attachment. Decreased range of motion, clicking or catching in the shoulder may also be present.

Treatment

Treatment will vary depending upon the severity of tear (partial vs full thickness), and patient goals (pre-morbid lifestyle and types of activities they will be returning to) as rotator cuff tears may often require surgical intervention.

Physical therapy following rotator cuff repair surgery will be dependent upon the post-operative protocol.

Manual Joint Mobilization: to restore normal arthrokinematics at the shoulder complex to reestablish non-painful ROM, and reduce capsular tightness

Strengthening/Stretching Program: targeting the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers emphasizing neuromuscular control of the shoulder complex. Postural stabilization and education are also important in reestablishing proper biomechanical movement.

Modalities: as indicated to reduce pain and inflammation at the shoulder joint

Authors:

ProOrtho

Samuel Koo, MD

Lake Washington Physical Therapy

Ben Wobker, PT, MSPT, CSCS

Jessica Paré, PT, MPT, OCS, SCS

References:

Orthopedic Physical Assessment, 4th Edition. David J. Magee, 2006. www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/92814-overview

Rotator Cuff Tendonitis

Rotator Cuff Tendonitis is an inflammation of the tendon and/or the surrounding peritendinous soft tissue. The most common muscle-tendon unit that is involved in rotator cuff is the supraspinatus tendon, and is often associated with Type II impingement syndrome. The shoulder is one of the most mobile joints in the body due to the shallow connection of the humerus (arm bone) to the glenoid fossa (scapula). The shoulder consists of static stabilizers such as the labrum, joint capsule and ligaments. Dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder joint include the rotator cuff, the long head of the biceps tendon, and muscles of the shoulder girdle. Tendonitis occurs when a tendon of the rotator cuff is inflamed and is compressed under an outlet in the shoulder known as the subacromial space. This space in which the supraspinatus, and biceps tendon pass under decreases significantly when raising the arm overhead causing a painful arc of motion when the tendons or bursa are compressed under the acromion process. This leads to overuse or repetitive microtrauma occurring in the overhead position contributing to rotator cuff tendonitis, especially among athletes participating in sports that require repetitive overhead motions such as swimming, baseball, and tennis. True tendonitis will typically last for no longer than 2 weeks in early presentation, but can last 4-6 weeks with a chronic presentation.

Symptoms include pain with shoulder movement, especially overhead. Palpable pain at the tendon is also present and shoulder weakness may occur.

Treatment:

Manual Joint Mobilization: to restore normal arthrokinematics at the shoulder complex and reestablish non-painful ROM

Strengthening Program: targeting the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers emphasizing neuromuscular control of the shoulder complex. Postural stabilization and education are also important in reestablishing proper biomechanical movement.

Modalities: as indicated to reduce pain and inflammation at the shoulder joint

Authors:

Orthopedics International

Vincent Santoro, MD

Lake Washington Physical Therapy

Matt Sato, PT, DPT

Ben Wobker, PT, MSPT, CSCS

References:

Orthopedic Physical Assessment, 4th Edition. David J. Magee, 2006. www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/93095-overview

SLAP Lesions

A SLAP (Superior Labrum from Anterior to Posterior) lesion is an injury to a part of the shoulder known as the labrum. The shoulder joint is made up of the humerus (arm bone) and its articulation to the glenoid fossa. The labrum is a fibrocartilagenous structure that serves to deepen the glenoid fossa of the shoulder thus creating a more stable joint. The SLAP lesion occurs at the point where the biceps tendon inserts on the labrum.

There are four classifications of SLAP lesions.

Type I: Significant fraying of the labrum in which the biceps tendon anchor remains intact.

Type II: Separation of the superior portion of the labrum and biceps tendon from the glenoid rim.

Type III: Bucket-handle tear of the superior labrum without biceps tendon involvement.

Type IV: Bucket-handle tear of the superior labrum extending into the biceps tendon.

Patients with SLAP lesions often present with shoulder pain that is difficult to describe but predominately located at the back of the shoulder. It can be associated with painful clicking or popping. This type of injury is commonly seen in throwing athletes but for the non-throwing individual, the cause may be due to a fall on an outstretched arm or a direct impact on the shoulder. Also a history of a sudden deceleration, such as losing control of a heavy object, may be a potential cause as well.

Treatment:

Non-Surgical Intervention: with emphasis on capsular stretching, and strengthening of rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers.

Post-Surgical Intervention: to be determined by post-operative rehabilitation protocol.

Authors:

Evergreen Health

Vincent Santoro, MD

Lake Washington Physical Therapy

Benjamin Wobker, PT, MSPT, CSCS

References:

Kim TK, et al. "Clinical features of the different types of SLAP lesions" Journal of Bone Joint Surgery Am. 2003 Jan;85-A(1):66-71. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1261463-overview

Disclaimer:

This website is an information and education resource for health professionals and individuals with injuries. It is not intended to be a service for patients and should not be regarded as a source of medical or diagnostic determination, or used as a substitute for professional medical instruction or advice. Not all conditions and treatment modalities are described on this website. Any liability (in negligence or otherwise) arising from any third party acting, or refraining from acting, on any information contained on this website is hereby excluded.